In the last years, predatory land flatworms have been introduced in many locations because of the trade of exotic plants. In this article published in Diversity and Distributions, a collaboration between iEES Paris, the National Museum of Natural History and James Cook University aimed to model the global invasion risk of these species. It turns out that they have not colonised all regions at risk yet, which demonstrates a need for increased vigilance in these areas.

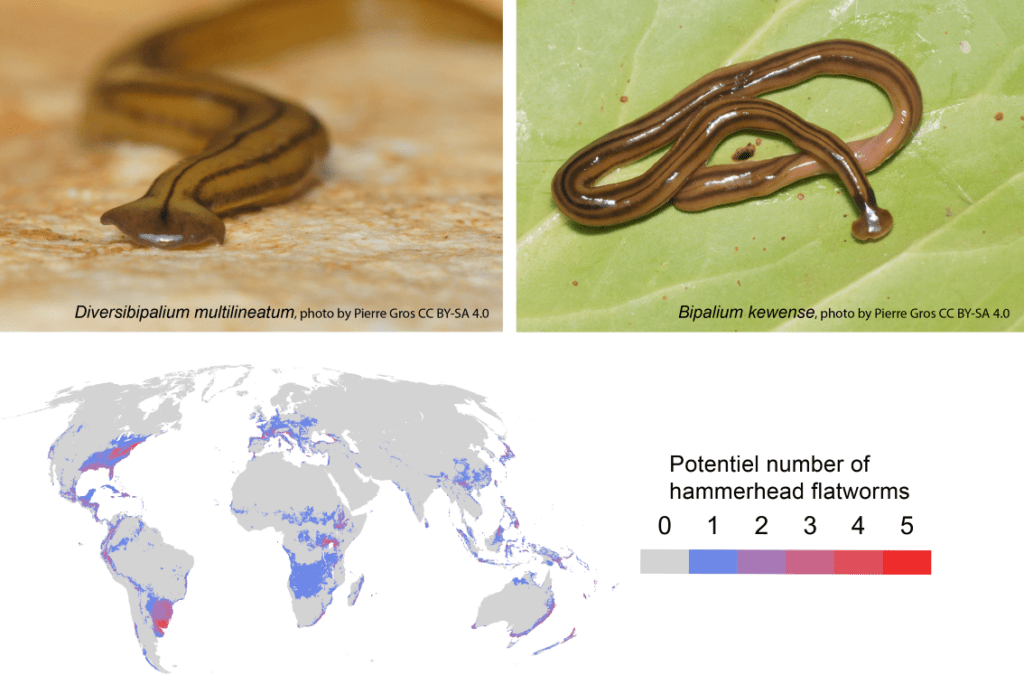

Terrestrial Platyhelminthes, or land flatworms, have established in France in the last years, most likely hidden in the soil or under pots of imported exotic plants. Among them, bipaliin worms, or “hammerhead” flatworms, are especially impressive; two species are found in Metropolitan France, probably originating from Asia, and globally five of them have been introduced outside of their native range. This raises concerns about their possible impact on invaded ecosystems. Indeed, the diet of these flatworms is composed of gastropods (snails, slugs) or earthworms, the latter being essential architects of the soil.

The most effective mitigation strategy is essentially to prevent their establishment before it is too late. In this context, this study aimed at mapping invasion risk for the five most frequently introduced hammerhead flatworms globally.

In order to identify the areas that could potentially be invaded, statistical models have been developed that relate flatworms’ observations (from citizen science records) and environmental factors, mainly climate. The objective is to determine the ecological niche of each species, and therefore to identify the most suitable areas where they may be able to spread.

Modelling results bring important evidence that can be used for managing invasive flatworms. In France, all five studied species could potentially find climatically suitable areas for their survival. Still, the only hammerhead flatworms that are actually present are Bipalium kewense and Diversibipalium multilineatum, which are remarkably large species (up to several tens of cm). The arrival of a new invader remains thus possible, such as Bipalium vagum, which is highly invasive in North America and in the French West Indies, and for which models show a high invasion risk in a large part of Metropolitan France.

Besides France, this study highlights other areas that could potentially be invaded. Remarkably, a small region of South America (the River Plate basin, especially Uruguay and Argentina), appears to be suitable for all five species. This area is a hotspot for many native land flatworms; it is thus important to prevent the introduction of potential competitors that could disturb these exceptionally rich ecosystems.

Since models predict invasion risk of flatworms as a function of climatic factors, it is possible to project this invasion risk in the future, depending on various hypotheses of climate change. Here, both species that currently have the largest observed introduced range (Bipalium kewense and Bipalium vagum) are predicted to benefit from a warmer climate. Therefore, invasions by hammerhead flatworms are not going to end anytime soon. For now, countries that show a high risk of invasion should be particularly careful, since eradicating those species from invaded areas will certainly prove difficult.

Another project, funded by “Agence Nationale de la Recherche”, is currently ongoing at iEES Paris. Its objective is to analyse the ecological impact of another introduced flatworm, Obama nungara.

Publication

Fourcade, Y., Winsor, L., & Justine, J.-L. (2022). Hammerhead worms everywhere? Modelling the invasion of bipaliin flatworms in a changing climate. Diversity and Distributions. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13489

Contacts

FOURCADE Yoan, MC UPEC à iEES Paris, team BioDIS du department DCFE

Jean-Lou JUSTINE, Pr MNHN à ISYEB, Institut de Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite